Sea and Sky

I took the money and moved to Connecticut. Dad wanted me to come back home, to stay put, but I had wanted to live in New England ever since Mom read One Morning in Maine to me as a child; it seemed so beautiful and solid. I became enamored of the Southport section of Fairfield when we stayed there during a tournament some while back, and the ocean vistas beckoned me back.

Never having been personally wealthy before, my bank account now seemed ever-expanding. I bought some stocks which brought in more. Secured the lease on a big clapboard house of an absentee writer in an exclusive enclave, one posh house after another strung along the curving beach like a stone circlet, the facades barely visible from the pavement beyond the long driveways, the backs facing out to Long Island Sound. Each massive structure blocked the sight of the water from the road; having bought the view for a hefty price, each homeowner felt it necessary to exclude it from vehicular gawkers. I settled down uneasily here to my self-appointed role of painter, vague do-gooder and lady-in-waiting for I wasn’t sure what.

Each morning I’d drive out to the General Store, the billowy ocean horizon reflected in my rear-view mirror, and buy a newspaper I didn’t read; each morning I’d set up my easel facing the Sound, hoping to catch some left-over karma from the former resident of the house, his last book having hit the bestsellers list. Each day the clock would do the work; each night I’d toss myself to sleep. A solicitation letter from Human Rights International came in the mail, and after a couple of weeks of looking at it lying on top of the other junk mail and catalogs on the front hall table every time I went out, I sent them a check, pulled off the sticker they had enclosed (“HRI” in black letters on a blue and white background) and smoothed it onto the bumper of my car. The world was now a safer place.

I went home to Ohio at one point; my sister, Maureen, had suffered a miscarriage, and Mom was worried about her. I talked to her, saying things (‘You and Gary can try again.’) with no notion of what was what, making it worse. In one respect at least I’d been right—returning here was not an option; the flat weariness, the dreary familiarity spooked me. I missed the motion, the commotion of the tour—without a final destination we were always bound for somewhere else, perpetual motion our saving grace. Two weeks was all anyone could take.

This time I brought Izzie back to Connecticut with me, forgoing first-class flight for a harrowing 17-hour trip in a rental car, frantic scratching, frightened and confused meowing issuing from the carrier on the back seat a good part of the way. “He’s too old for such an upheaval,” my father gravely warned, but again, I knew what was what. I missed the comfort of him, and after holding him again, petting him, fell upon the idea of starting my own breeding program. Perfect beauty in grace and form—I wanted to approach it. I contacted a local breeder of Birmans as soon as I settled in and bought a male kitten. Ben would be my foundation cat, Izzie having been neutered long ago at the insistence of my parents. All the pieces were now in place. I daydreamed great dreams of glory heaped upon myself: the famous painter interviewed in her lovely garden by the sea, with her beautiful cats, the faithful Izzie always by her side. (And don’t forget the HRI sticker on the car.)

But it quickly swung out of control. Izzie never adjusted to the move, trotting neurotically round and round the big house, sticking close to the edges; Ben was less healthy than he had originally appeared at the breeder’s house, and did not grow robustly. Isolated in a town where I knew no one, alone in a stranger’s house with only two cats for company—one crazy, the other increasingly frail; these were hard times. And then, just out of the blue, I saw Michael one night on TV. I had believed myself sheltered from any such blow by the religious avoidance of all sports media, but beyond niche famous now, here he was promoting a credit card company in prime time. Like Lazarus rising from the dead. Funny and larger in all aspects, he was riding high (Don’t you know me . . .?), grinning his predatory grin. I blamed him for everything. Everything. His onscreen charm rubbed our diverging fortunes in my face. How many girls, I could well guess, had succumbed by now to this seductive power.

My parents were concerned about their two girls. They were concerned about Izzie. They were concerned about my rattling around in that ridiculous house, self-destructing in a faraway place with no family or friends nearby to keep the mess contained. Even so, they underestimated the power of the undertow, the downward drag of the sense of self-worthlessness, the knowledge when drowning of your inability to swim only pulling you deeper. I walked along the beach relentlessly, as if understanding would eventually come with the accumulation of a certain mileage. Eventually, I’d sit on the sand, supposedly sketching or reading, but really just thinking, thinking, trying to think it through, staring out into the steely blueness till hypnotized, seagulls soaring and bobbing in and out of my peripheral vision, sandpipers skittering in and out of view. Hunkered down amid the tidal debris, the sodden sticks and broken shells, the shards of plastic cups and remnants of foam rubber, shrouded in jacket or blanket, I looked back over my past and questioned every judgment I ever made.

Ben died at the vet three months later, his heart arresting while undergoing anesthesia for an exploratory procedure. He was eight months old. He was born with a luminous soul but a cardiomyopic heart—no one supposedly knew. Izzie deteriorated and my vet ran every test possible, finally pronouncing the dreaded diagnosis of FIP—a guess, a death sentence. I vowed to fight this invisible evil; I owed it to him. In retrospect it would have been kinder to let him go peacefully. But how could I accept this? For a time, I lived in my car, plowing back and forth to the vet, a traveling misery show, forcing the vehicle forward through sheer will as much as gasoline. Mercifully, one night the door opened and Izzie left me, carrying his master’s soul into paradise as legend told me he would.

* * *

I took their ashes, head bowed as I trudged across the sand, swaddled in my winter coat against the bitter whipping wind, and walked out as far as I could on the jetty; the tide had turned and was coming in, but I had time. The ocean winds swirled around me, blowing my hair into my eyes and mouth, and when they turned out toward the water, I opened the box and stretched out my arm. A dusty cloud flew out of it, hung in the air, then arced downward toward the east like a flock of birds, falling on the heaving surface and disappearing. I stood there till I could feel the spray of the incoming breakers on my face. As I turned my back, burrowed in my grief, placing each foot carefully on the rocks in front of me, the spume grabbing at my heels, I thought I must be the loneliest person on earth.

I had been fortunate. I never had to face death before, never had to engage it in battle. I could not accept these deaths. I raged against them. I was terrified by them. I banged my head again and again against the brick wall of reality; I summoned all my mental and emotional resources, but I couldn’t get over or around it, that wall stretched in all directions to infinity, in time and space. And that wall was pressing in on me so that I could barely breathe. Finally, I gave in and let my feelings overwhelm me, wandering fitfully around the house, blinded by my tears and the remorseless sunshine streaming in through the windows, highlighting the vacuousness of my desolation. I snatched up various of Izzie's things, squeezing them to my face as if they exuded the only oxygen in the place and I was fast expiring. Hoping that something, anything, would gain my attention and give me a momentary escape, I kept the television running constantly on high volume to shatter the silence.

A day after scattering Ben and Izzie's ashes, a special report alert on the TV startled me like a loud knock on the front door: the space shuttle Challenger had exploded—one more sadness in a sad world. I became frozen, transfixed by the image on the screen, endlessly repeated, of the birds flying through the clouds of smoke from the explosion, clouds trailing down through the sky like spent fireworks, their beauty given up stupendously in one noisy flash, their entrails hanging down like popped party favors. Again and again they ran that image—the birds flying horizontally through the drifting smoky remains as if mocking the aspirations of the creatures below. The mystery of the universe—whatever you wanted to call it—was again for all of us an impenetrable wall, and I was able to take a morose and perverse small comfort in this.

I turned off the television. Exhausted, I fell asleep in the late afternoon with the radio on instead. When I woke up slumped on the couch, my mind fumbled in a never-never land for several minutes; I didn’t know where I was or what time it was, the sun had gone down, the house was dark. I had only been listening to news radio, my emotions were not under enough control for anything else, but now music was flooding the room—Brahms I guessed; I recognized it. The news day was over; I must have slept for several hours. So it was all a dream I thought with a rising sense, a long and bitter dream. Izzie would come out to me if called, and jump up on the couch, butting his head against me. Ben was still here, asleep in his basket. Even Michael the promotions man . . . he never really paid me to get off his stage, did he?

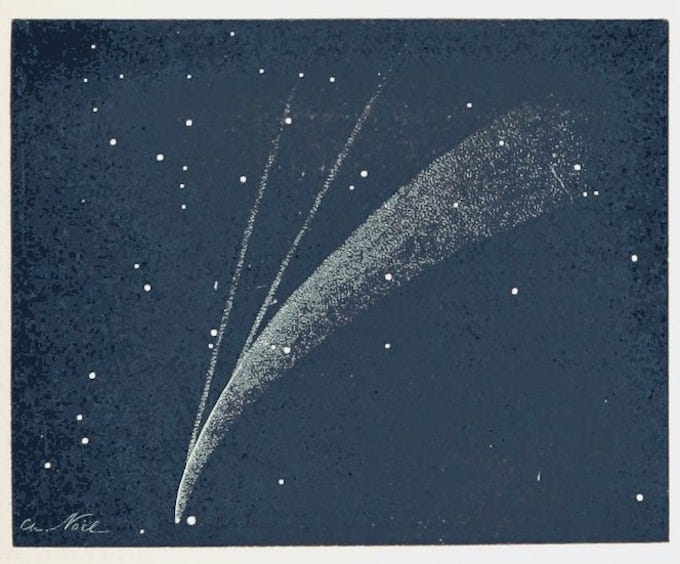

But my confusion cleared. The music swirled on, forming eddies in the room and purling at my feet, compelling the tears to spill once again. The notes summoned a vision—impossible, ridiculous to be sure—but as real as anything I’ve ever known of Izzie flying through the vast black universe toward infinity, each strike of his paw sending a shower of sparks flying behind him like a comet. I saw him just once again and understood. I moved to the dark window, rested my hands on the glass and looked up at the stars. Goodbye, Izzie. Goodbye. His soul was no longer struggling, pinned here on earth. The priest was released as well, on his way home. May you run through the skies forever.

Image: May you run through the skies forever. Source: British Library digitized image from "L'Espace céleste et la nature tropicale, description physique de l'univers ... préface de M. Babinet, dessins de Yan' Dargent," p 319. Paris, 1866. Edited by J. Weigley