What Matters Most

HRI’s New England Regional Office was housed in an eight-story office building just on the edge of the main Yale campus, near to the Daily News. Most of the other occupants of the old building, one of the few not yet torn down by the University, were small businesses or obscure departments of Yale. Our office was a suite on the fourth floor with a main outer room which served as the reception area; Paul’s desk was located there as well, along the back wall by the windows, behind the copier and fax machine. Off to one side was a short hallway; walking down it you’d find two offices on the left, the rear one Ross’; and, lastly, a large office on the right with the file cabinets, a computer, and a small conference table.

Six staff members, several volunteers, plus a vast array of comers and goers crowded into this space daily. Just as libraries are a haven for the homeless and a magnet for the strange, this type of work attracted the unhinged along with the seriously committed. High school students often worked with us, and were generally very enthusiastic, picking up the point right away. Then there was the tall, impeccably dressed woman with dark hair down to her waist who looked like Cher when Cher was with Sonny. She appeared one day wanting to volunteer, so I set her to photocopying and collating. Forty minutes later toner covered her formerly immaculate white suit. The unfortunate copier incident. The next day, I was told, she cut herself and bled profusely, causing a minor panic. We never saw her again. There was raven-haired Natalie, a rich kid undergraduate at Yale who wanted to be an actress. Grad students, seriously overworked, yet a great help. A few people who thought they’d hobnob with the brilliant and the famous. A few who wanted to save the world, but felt grunt work beneath them. A few women who, in the past, had always stayed home, but needing contact with the outside world, now chose a good way of going about getting it.

Ross was the regional director, in charge of the entire operation including coordination with headquarters. Also National Asylum Researcher, heading up HRI USA’s Detention Project, the Refugee Office being split with Ross and several volunteer activists conducting research here, and the administrative aspects handled in New York. Paul was the office manager, in charge of staff.

It wasn’t too long before I understood why Paul had been so hyper about the salary issue. Joanna, one-sixth of the staff, announced she was leaving and going back to school. She had been brought on board thinking she was going to have a paying job as a writer, but no money ever materialized from headquarters, and she was very disillusioned with the whole outfit. I felt bad for her, but her cynicism threatened my boat newly rising on the feel-good tide, and I was quite willing to toss her overboard. Standing around Paul’s desk, a few of us made a feeble, hurried attempt at organizing a small goodbye party for her. Nobody was able or willing to fork out a lot of cash for a gift. “We could get her a pocket calculator,” Paul suggested. All the women there simultaneously had the same silent thought. ‘How does his wife stand it?’

“You know, if someone’s feeling badly used, perhaps it would be better to get them a more personal gift,” I explained to him. It was too bad she was leaving; she was nice and she was the only female staff member—the other three women officially part of the office were volunteers: myself, the soon-to-be-famous actress Natalie Parillo, and Colleen.

Colleen Thomas, volunteer: everyone thought she was a sweet kid, but I could not abide her. I could see all my own foibles amplified in her, and I could not forgive her for them. She was pretty if you took the time to look at her—refined but not striking: medium height, medium build, medium coloring—and from the day she entered the office hoping for some validation of her convictions, some meaning in her life, she had fallen hopelessly in love with Ross.

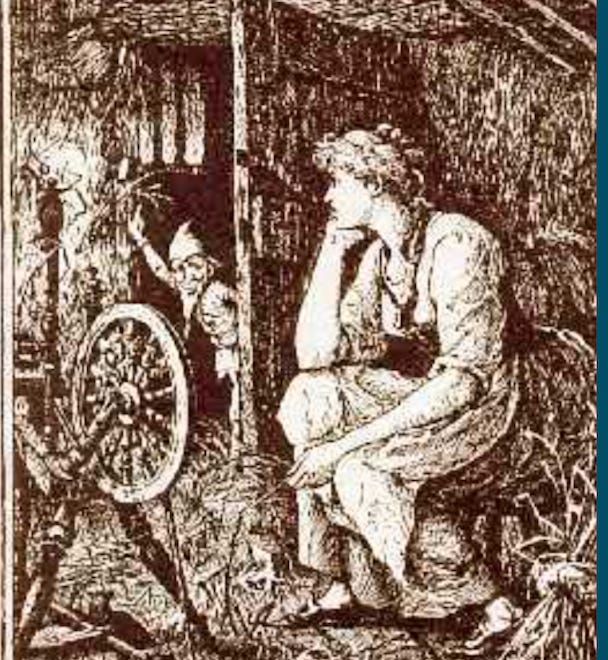

Her great talent—it helped us enormously—was getting people to do things when they would normally tell someone requesting such a thing to buzz off. It was a gift. She got copying jobs redone at no cost when we didn’t like the quality, she constantly finagled free toner and fax paper from suppliers, she paid for things using third-party checks and HRI letterhead, she even got expedited replies from United Nations offices. No one could deny her; apparently a lot of people had a soft spot for our mission and for her honest face. She had Ross and HRI behind her; she had the angels on her side. One of the fiercest straw spinners of all time. Paul enlisted her to turn the window air conditioner units on and off on half-hour rotating intervals to save money because she was the only person anyone would tolerate doing such a thing: no ego confrontations, no power-tripping. She could get people to do most things except the one person who mattered most to do what she wanted him to do.

* * *

Over time, as I worked there, I began to put together the pieces of the puzzle that was Ross Fowler. Some things Ross told me himself, though not very much. I knew he had grown up around Boston, in Brookline or Belmont, I think, and that he had a younger sister; other stuff I figured out myself. A lot came from Tyler Sheridan, the press spokesman in our office, an old family friend of the Fowlers and inveterate gossip. And a few choice items were revealed by Paul—the fact that Ross refused to use a seat belt—it’s a Massachusetts thing, Paul said. A lover of baseball, a long-suffering Red Sox loyalist in Yankee territory.

Tyler filled me in on Ross’ family background. The two of us went out to dinner one night after work at his instigation, and he drank steadily, becoming more loquacious, more eager to air his psychological acumen regarding his friend’s current emotional state—this coming from a man steadily letting the reins slip on his own life: divorced, seldom seeing his young son. “I’ll tell you the whole sad tale of the young Ross Fowler,” he said, “because you’re obviously dying to know.” He ran a hand over his balding head. “These tender-hearted women . . . he attracts them like flies. I on the other hand seem to repel them. Why do you think that is?”

“Because you’re a cynical lush?” I mumbled through my fingers, my chin resting in my palm. I didn’t like his tone where Ross was concerned. I took my hands away from my face and sat up straight. “Why don’t you eat something solid? Your liver’s probably already the size of Ohio—isn’t that good enough?”

“Ah, I see you haven’t come out with me this evening simply for the pleasure of my company. And I thought I was being exceedingly alluring.” He stared at me with the imagined insightfulness of the inebriated. “Ross had better watch out where you’re concerned,” he said, narrowing his eyes, poking his fork at me. “You’re very clever.” He paused, waiting for a reaction, but I refused to participate in the badinage. “So, you wanna know what makes Ross tick. Okay . . .

Let’s see . . . where to start . . . where to start . . . Ross’ father’s a professor of mechanical, no, civil engineering at MIT, a hard-ass, but not a genuine bastard or anything. Now his mom was a peach—brilliant gardener, could do wonders with green things, I remember. An artist, too; not much talent really, but she had an affinity for all things beautiful. Why the two of them were originally attracted to each other God only knows. There’s a younger sister still in Boston, Dorothy, named after the mother, some muckety-muck in public television—she’s responsible for all that God-awful begging. Everyone calls her Dottie. I doubt you’d like her, she’s very similar to her dad, whereas Ross is very much like his mom. Anyway, the important point is Dottie always sides with her dad against Ross. Ross desperately needs someone on his side, Ms. Templeton. Dottie married young, a doctor of some kind, and is into the social scene there, on the board of charities, chamber orchestras, you name it—the successful life, the good child. There will probably be grandchildren shortly. Are you getting this so far? Nothing too original . . .

I took a sip of my iced tea.

“I’ll take your silence as an affirmative,” Tyler continued. “The world changed when his mom died.”

“How did she die?”

She died when he was 15. Run over in the parking lot of a Newton mall by a gal who had one too many drinks during lunch out with the girls . . . Tyler half swallowed a burp . . . she’s walking toward Filene’s and this drunk just put her car in reverse, slammed on the gas and mowed her down. How do you deal with that when you’re 15? Anyway, the father and son turned against each other after that. Ross never forgave his dad for the way he treated his mom while she was alive. Herr Professor never forgave Ross for being so much like her, and for all the unspoken accusations. You see, I’m sure his dad loved his mom, but he’s the type of guy who believed admitting it too often was a sign of weakness. Perhaps you’re familiar with the type? He ridicules people as a way of showing affection. I think Ross might’ve eventually come to an understanding of this when he got older, but . . . too much water under that bridge. I know he grew up resenting his father because he felt nothing he did was ever good enough. And great things were expected of him; his mom couldn’t protect him from that. And then she died, and they were devastated. . . but they couldn’t reach out and . . . dad turned to Dottie, and they grew apart until now they can barely be together for half an hour before there’s some kind of blow up. He might have broken a weaker kid, but as you know, or will surely come to know, Ross is the most stubborn s.o.b. on the face of the earth.

Tyler leaned back in his chair and caught his breath as the waiter cleared our dinner. After ordering me a coffee and himself another Scotch despite the faces I made at him, he continued, drunk and chatty:

The old man believes everything Ross does he does simply to annoy him. He wanted him to go to Stanford or MIT, major in math, physics, be him basically, but Ross decided to major in history—for spite, you know—and ended up at Brown. He and yours truly had a stranglehold on the school newspaper there for two years. We were terribly dogmatic back then, not like today. He went on to Yale; I went on to Columbia.

Tyler’s voice got less and less audible, and a far-away look and strange smile crept onto his face. He sat staring off into the middle distance, head tilted down and to the side, silent for so long that I became convinced he had blacked out open-eyed in this position. Just as I was beginning to panic at the thought of having to physically remove him from the table, he looked up and continued:

And then after law school, a lot of firms wanted him, but he went to work for a year or so in New York with a legal defense outfit and then fell in with HRI. Actually, he was recruited personally by Robinson. That’s about the whole story . . . Ross has always hated his father’s theory of growing up cold in America, but Dad succeeded in planting the fear in him of looking like a wuss, of becoming “earnest” like his mom if he dares to live with his true feelings on his sleeve like she did. And like all stupid fears implanted against one’s better judgment, this one has apparently taken hold and still grips deeply—our friend’s extremely defensive of his innermost emotions, I warn you, and has become lately, I think, something of a stoic. Just too damn painful to lay your guts out there on the chopping block.

So there’s . . . oh, yeah, speaking of being eviscerated, I almost forgot about Donna, Donna S. Pokalski—God, she’d eat you for lunch. She and Ross met at Brown and went on to law school together—it was cute back then. They lived together for, I don’t know, two, three years? They started off madly in love—she’s quite striking, y’know—but over time she turned on him, turned amazingly into his dad, except she’s much nastier. It’s sad, really . . . she wasn’t always such a bitch. But you see, that’s just it—that’s just it! Don’t go and get all huffy on me. Here’s Ross all bruised and needy, with those lovely sad eyes, and it draws women in droves; it’s a fucking aphrodisiac. But I don’t have a high opinion of your gender, if you’ll forgive me, because eventually they realize that Ross is not a puppy or a doll, but a very bull-headed, serious, and dare I say it, not very wealthy or conventionally successful man, and they back away. They’re not in it for the duration; they’re not in it for the reality—they actually dislike the reality. They don’t want to heal him; they want to fix him . . .

“Let me pay my half,” I said, anxious to exculpate my sex, as Tyler, wrapping up dinner and his story, took out his wallet.

“I wouldn’t dream of it,” he said, handing the waiter his credit card.

“Well, thanks then. Thanks very much. Let’s make sure we get you into a cab headed in the right direction, okay?” Taking his arm, we walked out of the restaurant, the former reporter leaning heavily against me whenever he momentarily lost his balance. I turned to him; his breath almost knocked me down. “Well, is your curiosity satisfied? Do I pass inspection?”

He smiled sweetly at me, “For now.”

Image: The fiercest straw spinner. Source: "Rumpelstiltskin", by Henry Justice Ford, from Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book, 1889. Edited by J. Weigley