EPILOGUE

Emily’s Bell

It was a year or so ago that I, Kenneth Kilmer, bought the small farm from the estate of Henry Stoughton. There was a ramshackle shed on the property, overtaken and brought down by bramble, the boards in the drywall rotting up from the ground, producing gaps large enough for rodents to enter. Abandoned acorn caps covered a work table with a vise clamped to its front edge, along with mouse droppings, and the remnants of cracked hickory shells from the ghosts of children who worked that vise long ago. Despair emanated from the very wood of its walls, as indelible as the faint smell of alcohol that permeated the place. Death was close here, too, and time ticked loudly onward with one's own heartbeat, raising panic in the souls of those who lingered too long inside, which was why none of the locals had bought the property. On his last day, Henry Stoughton rose from his deathbed, they said, and being a farmer, a man who lived in the free air, struggled to escape his confines and will himself outside to draw his last breath in the open. But he did not collapse upon the ground, eyes focused permanently toward the sky, the story went, he staggered to the shed and passed there with his demons, discovered later by one of his nephews.

And there must have been some two-bit fairground or carnival park in the back fields. There was the ruin of a train engine, not a toy thing exactly, but the damnedest thing—as big as a small horse—rusted into its tracks. These tracks, which I only discovered by stumbling over them, serpentined throughout the far right pasture; the ties now sunk under the soil, the rails almost level with the ground, and most of it obscured by clumps of weeds from which white cabbage moths emerged, fluttering and bubbling above their green grass cauldrons. Impossible to mow, and it would be hell trying to remove it. Not to mention the cost. That's why I agreed to let Stoughton's niece board her horse here. She contacted me not long after I bought the place. I had no wish to get entangled with some animal rescue outfit, but she seemed a quiet enough gal. Her rent would pay for removing the last of her uncle from these fields. My fields now, my land. I was itching for it all to be done, but pulling out Stoughton’s last clutches hurt some part of my psyche. Whatever happened here remained palpable. What was this history that refused to let go of its grasp on the place? People said it was spooked. My mind arced back constantly in curiosity to its provenance. Had there been a happy man here once? I closed my eyes and opened them, imagining I was Henry Stoughton waking up—young and handsome, death not yet knocking, the train still running, at the very start, at the beginning.

But it was beyond the end of the start, and at a new beginning. The date was set for the girl to bring her horse, and I stepped out to the front stoop that day when I heard her van turn into the driveway.

But it was a car that pulled in instead. I was waiting for a trailer and a horse, and the lone car confused me. A young woman got out and silently approached me.

"Where's the horse?" I called out to her.

She froze for a second, her wide-set dark eyes looking off to the side. Then without moving her head, she turned her gaze on me and whispered, "Excuse me?"

"The horse. Where's the horse?”

"The horse? I'm Emily . . . " she said, swallowing her last name so I had no idea what it was. "My father used to bring me here so I could ride Mr. Stoughton's train when I was little. Sorry, I don't know anything about a horse. I knew the place had sold and, so, was hoping to . . . I drove here today,” she made a waving motion with her hand, “just to drive past." I could see the memories, shadows of fast-moving clouds, glide across those eyes. "Those were happy times," she said in a louder voice.

Yet one more claim from the past. "Yeah . . . well, I was expecting someone else, that's all. Have a look ‘round if you want, if you don't mind ruining your shoes." She was hesitant, so I motioned her to go ahead, and the two of us walked out into the field and stopped at the fence surrounding the back paddock. “So, what was all this?” I asked, gesturing at the train engine.

"It wasn't anything official or anything like that. Mr. Stoughton took kids around the field on his train. Any kid that showed up. And he had horses. But it was more than that. It's hard to explain. It was summer; you were a kid. Everything smelled, good or bad; everything was tangible. You were riding the train, and the sun was hot and brilliant, and the possibilities were endless." I didn't know what to say to this, so I said nothing. She leaned on the railings and stared across the field at the engine, a jarring black-brown blotch amid the yellow-green weeds. So still and bleak it was hard to believe it had always been inanimate, so steadily did it now emanate its mortality. I think Emily what’s-her-name was sorry she'd come back.

"Seems so small now, not like I remember. They shouldn’t have let it go like this."

"Well, a gal is coming today, any minute, to board her horse here. It was her uncle’s train. The rent will pay to have it junked and the tracks removed—it’s a hazard now. That’s the horse I was talking about. One of those Lipizzaner horses like in the movie; they stand on their hind legs and stuff. Anyway, all the way from Yugoslavia." I paused; I didn’t know the full story, but I knew the story was bad. “They were starving them there.”

"Yugoslavia doesn’t exist anymore."

"Bosnia . . . whatever. Somewhere around there."

* * *

And, indeed, at that moment, a horse van carrying Tulipan Capricia, one of the stallions recovered from the destruction of the Lipik stables, was being driven by Henry Stoughton’s niece up VT100-N on their way to the Kilmer farm. Miraculously, she had found a music station on the radio up here in the red spruce mountains, but it was beginning to fade. “This was Enesa’s favorite song,” she said over her shoulder to Capricia, whose head was visible through a window behind the driver’s seat. He made no comment. “I know you loved this song, Enesa,” she continued, addressing the empty air. ‘Even though you seldom listened to it; it made you feel too much. You always put it on mute.” Neither did Enesa answer her, because Enesa Marić was dead. Assaulted in her home; murdered in her bedroom as she sat spinning her dreams. This was the hard truth, but Capricia’s driver that day could not accept it, and so it did not stop her from carrying ongoing conversations with the absent girl. “How you loved the possibility of love . . ..”

This was what was left for her now: communicating with her ghosts, and she took comfort in the simplicity of it. The striving was over. Her friend Richard, she knew, would challenge her, but she would counter right back. ‘You reduce everything to physics and philosophy,’ she would tell him. ‘You’re all calibration and cant.’

* * *

Emily released her grip on the fence and took her foot off the bottom rail. “Well, thank you, Mr. Kilmer, thanks very much for your time.” She turned to head back to her car then stopped and faced me. “Would you mind if I took a little something back with me?" she asked.

"Like what?"

"Oh, I don't know, some dirt, some part of the field?" I looked at her. "Okay, well, maybe part of the train? Yes—the bell! I didn't speak as a child, actually, but I rang that bell. I really, really rang that bell."

“Let me see what I can do,” I said, at this point sucked into the old train’s spell and not fighting it. I jogged back to the house, coming back out with a screwdriver and a hammer. As I thought, the screws were rusted solid and wouldn’t turn, but using the screwdriver as a chisel, I was able to knock the bell off its mount. I handed it to her, and she held it up aside her head and shook it, but the clapper was gone. “Why didn’t you speak?” I asked her.

She lowered her hand and let the bell rest against her chest. Again her eyes turned away from me. “Thanks," was all she said.

We headed back slowly, past the abandoned shed. The van I had been waiting for turned into the driveway and came to a stop. It rumbled in place until the engine was shut off. Stoughton’s niece jumped down from the cab, and came forward to shake my hand. She was shorter than I expected, with coppery hair pulled back off her face and her right forearm enclosed in some kind of carpal tunnel brace-like thing with an abundance of Velcro. Her glasses sat crooked on her face, but she removed them and put them back in the van on the dashboard. She went to the side of the trailer and proceeded to open a number of locks, making loud clicking and slamming noises, lowering the ramp. She disappeared inside for a few moments, then emerged leading the massive Lipizzaner. The horse looked huge, the girl small beside him. The stallion, snorting and shaking his head, was led around to the two of us.

“Here he is: he’s called Tulipan Capricia, after one of the stud lines."

"Tupelo Capricia—fancy—like a racehorse, eh? Not Soldier or Star or something.”

"Tulipan, not Tupelo,” she corrected me. “We usually just call him Momo." This was said without a trace of either irritation or patience. Don't know what happened to her over there, but she gave the impression of living now to carefully put one foot in front of the other.

I opened the gate for her and the three of us walked back with Capricia to the paddock where Emily and I had been standing. I introduced Emily merely as ‘Emily.’ The two women after a moment seemed to recognize something in the other.

“You’re not the little girl whose father used to bring you to ride the train, are you?”

“Yes, that was me. The one who never spoke. Mr. Kilmer here has been kind enough to let me have a last look. I heard your uncle had passed, and I just wanted to see the place one more time.” She paused, staring to the right into the adjacent paddock with the engine. “It has haunted me.”

A small smile of understanding passed between the two of them. "I’m so sorry about your uncle,” she continued. “He was always patient with me.” Emily switched her bell to her other hand and lowered her voice. “But he often seemed sad. Was he? Actually, I used to think we were somehow connected in some sort of secret way. Both good at hiding things. Both okay as long as the train kept moving.”

The other woman seemed struck dumb for a moment by this confession. But she answered calmly, slowly, speaking more to herself than either one of us. “Yes, my uncle was unlucky in love. He fell in love with . . . with a woman like quicksilver. Here and gone, but his heart held fast. Well, what can you say . . . haven’t we all loved and lost? People here and gone, and now this train soon history. And, it was all so real! Where does it go? How can it just disappear?” She narrowed her eyes as she stared across the fence at the train; her horse nodded his head up and down and pranced in place, lifting one hoof, then the other. “I’ve seen so much. Done too many stupid things. Why we haven’t wiped ourselves out by now is a mystery to me. How can we still be here and not have turned everything into some gigantic wasteland? Everything beautiful gone extinct. Extinct like the rhinos.”

"The rhinos aren't extinct."

"No, no they're not. Not yet anyway,” she had to admit. “My uncle’s love was a great love, I’ve always liked to think, like a countervailing force, an undying truth. That's what won't let go here.” She kicked up dirt with her boot, unconsciously mimicking the pawing of her horse. “Still doing battle.”

“And now and then, there’re survivors.” Emily said, again holding her souvenir up next to her head and ringing the soundless bell. “Like me.” Standing back from them a little, arms folded, detached, I smiled and dipped my head in a fleeting bow of agreement. “And him,” Emily continued, gesturing at the giant horse now struggling against the hold on his halter and jerking Stoughton forward and back. Stoughton lowered her head to hide an unanticipated surge of emotion, then jerked her head back up and looked at her Momo, her star. She slipped off the halter and let him loose. He loped through the open gate into the paddock as I stepped up to stand between the two women. And through the type of light found only in the mountains of Vermont—and, they tell me, Italy—the three of us watched Tulipan Capricia canter in the free air over Henry Stoughton’s fields.

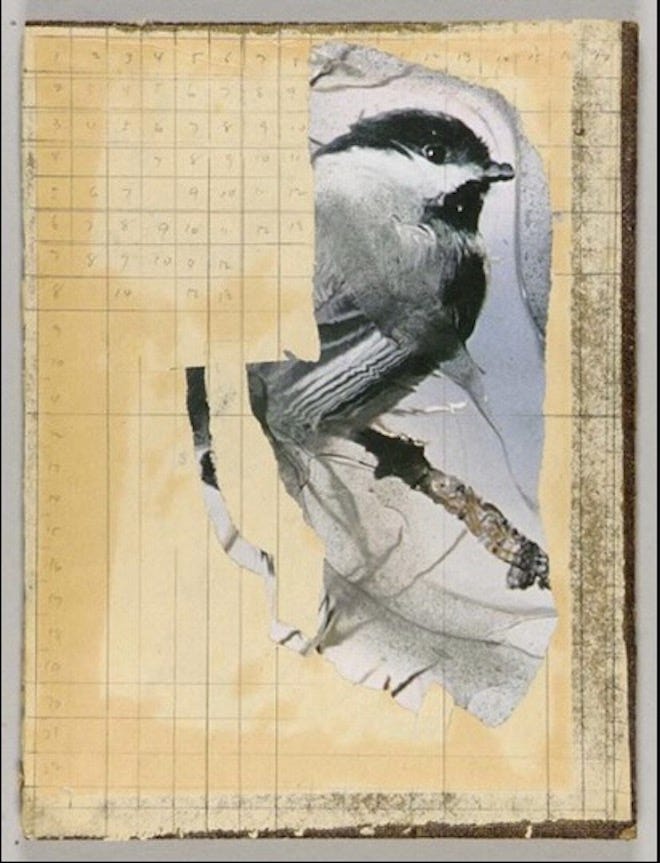

Image: Calibration and cant. Source: Joseph Cornell, “Mathematics and Music (Chickadee on Tree Branch),” 1967, collage, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, 1991.

Three great interwoven stories!