Greenwood Pizza

My palms were red and burned from all the clapping. If I had wanted to be first out of the block, however, I was too late, for after having taken several questions—one or two of them cripplingly cynical—the speaker was now shaking hands and talking to the lingering audience. That boy standing there next to him wasn’t about to let go either, I could tell. The boy with his head in the stars, looking up to Ross, eyes burning bright. He stood ready to pounce every time anyone paused for breath, and I disapproved of him, his eagerness trampling over whatever it was that had been conjured here tonight. The man at the center of it all patiently listened, spoke with everyone in turn, his manner grave and polite, his actual thoughts about it all unreadable.

There were only a few stragglers left when I got up to leave, pulling my coat off the back of my chair. His words had left me in a thoughtful, subdued frame of mind. A lot to contemplate, compelling company for the walk home. Ross saw me get up and interrupted his young admirer with practiced skill, putting his hand on the kid’s arm, breaking away and coming over to me. He said quickly, “Can you stay for a minute? I’d like to apologize for earlier. Maybe we could get a cup of coffee or something; I haven’t eaten.”

“Oh, sure,” I said. (Are you kidding?) “That would be nice.”

“Great,” he said, gently smacking his palm with his fist as if that was easily accomplished, a gesture I didn’t care for, then half-walking, half-trotting back to his remaining fans.

After a few more parting handshakes and promises to undertake great things, it was just Ross and the boy. The volunteers were cleaning up, unplugging the coffee, stacking the folding chairs. I couldn’t guess how long he’d be and felt stupid just standing there, so I motioned to him that I’d wait out in the hall. Alone there for the moment, I paced the entryway, the floodgates of expectation wide open, my agitated mind and heart racing each other without restraint.

Finally, he must have had enough. The kid left, giving me a sidelong glance, and Ross came out fiddling with his scarf and papers. “Sorry about that.”

“This is the second time tonight you’ve apologized to me.”

Ross didn’t know how to take that and didn’t answer directly. “I told you my name, but you never told me yours.”

“Amy, Amy Templeton.”

He smiled, “Well, Ms. Templeton, how about Greenwood Pizza? Do you mind going there?”

“No, that’s fine.”

“Good, my car’s parked out back.”

“Oh, we’ll have to walk. You’ll never get a space. It’s not very far.”

“Right. Let’s go.”

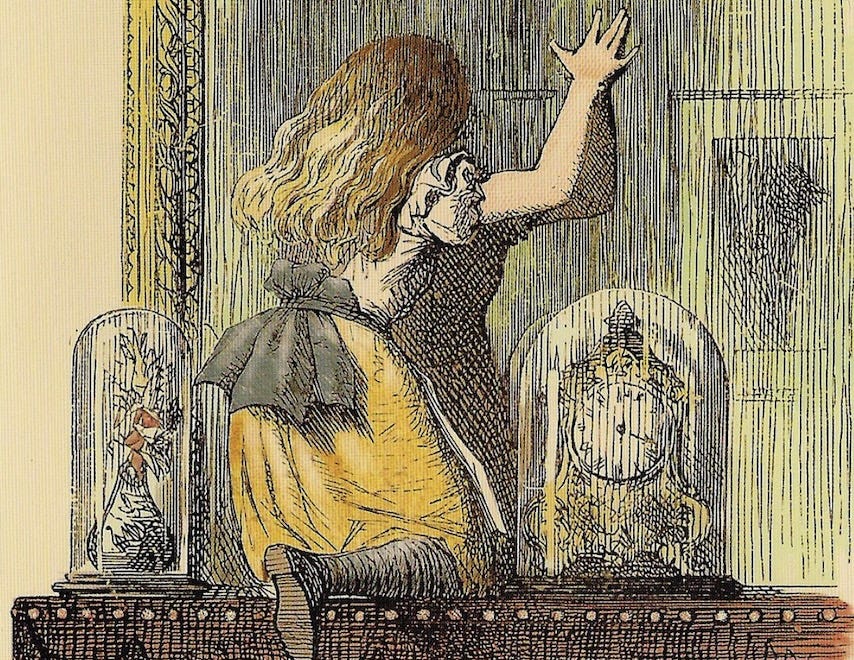

We went out through the basement door, up the steps into the night. It must have rained during Ross’ talk though showers weren’t forecast. Outside the dark streets were wet, mirroring the multicolored lights and a fresh wind was blowing the dampness away. The phantasmal scene glimmered and twinkled, reflecting my state of mind. Just like Alice pushing herself through the glass, we had stepped through to the other side it seemed, into a transformed street world—everything familiar still extant but with a slightly charged and fantastic quality to it. Even ordinary things, even me. So we walked up the side streets through the shimmering lights and mild air, sidestepping the puddles, up to campus, an underlying lightness to our gait.

We arrived at the brightly lit and crowded Greenwood Pizza. Music was wafting, a steady beat pulsing from Toad’s Place up the block. That crowd was just starting to filter in, a small group of poseurs already clustering outside in front of the window. I followed Ross into Greenwood; we were lucky and got a booth without too much waiting. There, sitting across from him, face to face, I could study him with impunity: the curves of his mouth, the reflected neon sparkling in his eyes whenever he turned his head. I almost could not process it, and with emotions already stretched tight, I was jittery with excitement, flushed and wrought-up. I had met my match and I could only wonder at it.

“It’s warm in here, isn’t it?” I said, fanning myself with the menu. Our knees inadvertently bumped under the table.

“Well, it’s crowded, but the food’s good,” Ross said, shifting his body slightly, scanning his copy. “What‘re you getting?”

It was crowded, and I was happy to be in its midst. The air was steamy and pungent with the smell of garlic even though evening air poured in every time someone opened the door. A longing to capture the colors on canvas, the yellow ocher of the hanging atmosphere, the espresso night outside, stirred from a long forgotten place. Our order arrived: gyros and coffee. Everything and everyone pleased me. The coffee had the dizzying kick of wine. The clientele chatting away over the background beat of jukebox music were all on the verge of greatness; someday we’d look back on this night and say, ‘Remember when . . .’ The waiters were witty, the cook and cash register guy running the busy counter like the United Nations. Ross took off his jacket, rolling up the sleeves of his corduroy shirt, and as I guessed, its slightly discolored label confessed it was not a recent purchase—from the fifties perhaps, his father’s maybe.

“Well,” I announced inanely, “I’m so glad I came to hear you tonight. I thought what you said was . . . great. And needed to be said.” No discernible response. “Was it a good turnout?”

“Pretty typical,” Ross said through a mouthful of gyros. Swallowing, he continued, “It’s frustrating, though, ’cause basically I’m preaching to the converted. The ones who need to hear aren’t listening.”

Ross was no flirt. He was reserved and his conversation remained focused on his work, never straying into the personal. He seemed more interested in his food than in me. At certain points I could tell he was thinking, responding in his mind to something I said, but in the end never saying anything out loud.

I was beginning to have to work at it a little bit. We had nothing in common in our experience; why would he be interested in anything I had to say? I had nothing to offer, only things I wanted to take. “So what’s next for you? Are you going back to Central America?” A stranger rudely familiar with his past, sticking her nose in where it was none of her business.

“No, not in the near future. Actually—you’ll be interested in this—HRI is planning to open a New England regional office here in New Haven sometime this summer.”

“Really? Why New Haven? I would’ve thought they’d put it in Boston.”

“Well, for several reasons. I’ll be heading it up, and my contacts are here just as much as anywhere else. It’s close to New York, and I’m still going to run some things out of there. We’re planning to set up a national Refugee Office; but we’re not sure yet how or where. We’re just starting to get that going.”

“So you’ll stay in New York.”

“No. I’m here already—in Milford. Right on the water. Sort of cool . . .”

“Oh.”

“I think it’s a good idea for us to get out of the clutter of all the various groups in Boston. Professor Atkins, one of my old professors at the Law School here, is going to push some of his students to work on field studies with us, and we’re trying to get Yale to give us some office space and support—yeah, good luck, right? I know. Basically, except for a skeleton staff, we’re gonna have to rely on volunteers.”

Ross became increasingly animated, his face brightening as he spoke of his plans, and the looking-glass world shuddered with an earthquake jerk back to reality, disillusionment curling its chilly fingers around the back of my neck as I realized he was recruiting. Sure enough, next came the dreaded, “So what is it that you do?”

Sitting across from me was a person who, I imagined, could be living a predictable, cushy life instead of risking it doing the heavy lifting, struggling without much reward to make the world a less terrifying place. What was I suppose to say I’d done so far? ‘Oh, I used to date a tennis player, kept him on an even keel if you know what I mean (wink),’ didn’t seem quite it. I squirmed, having no adequate explanation for my existence. “Well, I just moved here a little while ago,” I hedged, twisting my hair with my fingers, a nervous habit I thought I had dropped long ago. “I’m working at Sterling, for now anyway. I . . . I do a lot of cataloging in Spanish, you know, for the Latin American Collection . . . thing. I majored in Spanish, so . . . yeah, stuff like that,” I added, desperate to give my situation some sheen of adequacy.

If Ross was disappointed I wasn’t Joan of Arc, he had the tact not to show it. He plowed forward; he was good at this. “Ah . . . necesitamos gente.”

“You need people?”

“Sí, voluntarios. We’re not in a position to offer paying jobs. Your Spanish skills would certainly be helpful to us; particularly in regard to refugee issues . . . that would be great. Do you think you might want to give us some time once we’re set up?”

‘Your Spanish skills would certainly be helpful . . .’ The colors and shapes blurred around me, sucking me back into that hotel room once again facing Michael across the table. (‘After all, you gave up your job prospects to join us . . .’) The same formality of phrasing coating the barefaced request. The similar placing at a distance, the solicitousness that felt like a slap across the face. Confusion ricocheted painfully between my head and heart. I was wounded by having the squeeze put on me like this, but why? What had I been going on and on about? A golden opportunity dropped right in front of me. I didn’t know what I wanted exactly, but I didn’t want this.

“I’ll think about it,” I said coolly, effectively putting the kibosh on any further conversation. Though there was no question I’d be there when they opened the doors, for some reason I just didn’t want to give Ross the satisfaction. I didn’t like being pegged so easily. I wanted to be more important than just one more lassoed volunteer, roped in and added to the stable. Unflattering images of myself flashed through my mind: going to the lecture solo, staring like I did; I must have come across as desperate, demented. A wave of humiliation flooded over me at this nasty self-revelation, the smell of the picked-over onions on my plate nauseating me. Sickening me. Sick of being nothing, sick of not having the things people immediately and without thinking wanted.

Ross nodded soberly, pressing his lips together, raising one eyebrow just perceptively in surprise at being shot down; he had taken on faith that I was interested in becoming involved; he had no idea I was looking for something much larger. He had no idea the long path I had taken to get to this point, the struggle just to get to the starting block. Rebuffed, he reverted to his reserved nature. An old acquaintance stopped by our booth to shake his hand and catch up. I sipped my coffee, now cold and bitter, just to hide my face.

The merry spell was broken, the magic lost, sliding back through numbness into leaden disappointment. God, he could certainly turn the charm on and off when he wanted to. Why did this hurt so much? It hurt because he made you want to be with him, be like him, be liked by him, but, see, you could not reach out and actually touch him. This is what he does best, most likely, rounding up the lonely to burn off their longing through hard labor, like princesses spinning straw to gold for the cause. They’re easy to catch and there’s always a goodly supply of them.

The check came and Ross paid. “Did you drive?” he asked, sticking his wallet back in his pants pocket.

“No, but . . .”

“I’ll take you home then, it’s getting late.”

“Really, that’s okay, I can take the bus—it’s safe,” I countered hastily. “It’s not that late; I don’t want to put you out.” I looked at him helplessly. “Thanks for dinner.” My one desire was to get away, take my finger out of the candle-flame.

“No, no . . .” he took a deep breath, holding it a second, shifting in the booth, rocking slightly forward and back while exhaling. He looked tired, eager to give it a rest but unpracticed at taking no for an answer, unused to simply leaving the chick at the curb or calling a cab; when he leaned forward the light accentuated the circles under his eyes. “It’s no problem.”

What a different walk back to the church. I had approached that church earlier this evening with brilliant expectations. Ross had met those expectations. Walking up to campus with him, my dreams—tended so carefully over the years—were finally blooming, wantonly wide open. On our way to Greenwood, Ross at one point, still buzzed with energy from his talk, leaned over toward me and looking at me closely said, “I see your head’s back to normal.”

“Oh yes,” I had joked. “All clear.”

Now we retreated, retracing our steps back to the parking lot, the streets dry and offering no reflected beauty, just the accumulated litter of the day. It wasn’t going to happen here; it wasn’t going to happen tonight. A slight awkwardness rose between us; not willing to give what the other wanted, we’d run out of things to say. But the voice inside my head was going full blast, calling me every name in the book. I was paying for my conceit in assuming I could through sheer force of will mold Ross into the person I wanted him to be without any input from the man himself.

Ross unlocked the car door for me. The passenger side of the front seat was full of notebooks and papers. “Just throw that stuff in the back,” he said. He smiled slightly in apology for his lackluster manners and put his hand on my shoulder for a second, relenting a little toward me as if his disappointment was his own fault for expecting too much.

Because Ross had seemed deliberate, almost Quakerish in his manner throughout the evening, it was a shock when we got in and I was immediately thrown back against the seat as he jerked the car in reverse and then forward and sped out of the church lot. I turned frantically toward him for an explanation, grabbling for the seat belt jammed into the slit at the back of my seat, obviously seldom used, but his eyes were intent on the road. I wanted to ask, ‘Is there a curfew I’m not aware of?’ but I didn’t know him well enough for that level of sarcasm. I was spent by my emotional rollercoaster ride and, along with disappointment and exhaustion, visions of a head-on collision were giving me a stabbing pain between the eyes. Following my directions, we managed to arrive safely, screeching to a halt in front of our house just as I snapped the still twisted and far too tight belt into place. I freed myself and tore a scrap from the corner of one of his newspapers. “Here’s my number,” I said, writing it down. “Call me when you open the office, and I’ll see what I can do.”

Ross took the piece of paper and put it in his shirt pocket. “Thanks. Okay . . .so . . .” He turned and looked out his window and then back at me. “I’ll just wait till you get inside. Not sure what’s going on over there.” He jerked his head toward the opposite side of the street. I spun around, head throbbing, but saw that it was only Adam, sitting in his car waiting for Meredith. I didn’t try to explain. We shook hands, a little sheepish at the gesture, and I went up the steps and inside the house. I stuck my head out the door again and watched Ross speed off into the night . . .

Inside the overdue bills lay spread out still unpaid on the dining room table, waiting for Jean’s share, but she was out of town till Friday. I could hear Janet laughing with yet another man in the kitchen—there’d be one more stranger sleeping in the house tonight. And, of course, Adam ergo Meredith. Fed up with everything and everybody, I avoided human contact and tiptoed up to my room, closing the door quietly behind me. Picking up the Boston Interview article on Ross off my bed, I sat down, holding the paper to my chest; I sat frozen in this position for some time.

Image: Through to the other side. Source: John Tenniel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Edited by J. Weigley

I like this because it's so true to life. We idealize situations and are disappointed when life inevitably intervenes.