Stargazer

My warm and dreamy reflections on my lover are broken by the clicking and clanging of fork and spoon against dish and bowl, as in the other room my family scrape away at the last of the always too little food.

“Very dramatic, Enesa,” I said, flipping the diary shut.

“It’s just the way I write,” she shrugged her shoulders. “Someday I’ll write a movie about me, about my life. Andy Dorenberg will star in it.”

“Well, he’s a singer, not an actor, though if you’re famous enough, they’ll let you do anything, I suppose. It’s annoying. Actors singers, singers actors. Do what you’re supposed to do, I say.”

“I’m sure Andy can do whatever he puts his mind to.” Here Enesa flicked her hair out of her eyes with her fingers, a slight look of annoyance passing across her face.

Enesa Marić was a sixteen-year-old girl living in a small village between Jajce and Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Enesa Marić was a lover of language and music, and Enesa had been in love for years, it seemed, with the American singer/songwriter, Andy Dorenberg. When she found out I had been at some of the same festivals with him when Jay and I were together, she grilled me for every last possible iota of information. I told her many times I had only spoken to him once or twice, but for her this didn’t matter. I had been photographed with him, so that was that. For all her self-proclaimed sophistication, her idea of America remained one of a troupe of rich people all shopping at the same stores, all friends, all lovers. She didn’t understand the odd complexities that engulfed so many there as well as here. Only her world was comprised of pissing rain and mud-smeared angst; America was all candy and smoke machines.

“Tell me again,” she would say.

So each time I visited Enesa and her family, I needed to repeat like a mantra, “Well, Andy’s cool, as you know. All the women fall in love with him, and he’s funny.” She always tried to extract more from me than I had, but was ecstatic with whatever she got.

And then, dutifully, I would explain as well that it wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. I’d tell her it was basic bartering; people were commodities. I’d tell her the tale (her mother would banish me if she knew) of Howie yelling, ‘Welcome to the NFL!’ right in my face after a most unromantic grappling session in an Indianapolis hotel room.

“To say such a thing at sexual climax,” she would muse. “I don’t understand American football.”

Enesa’s love burned on bright and pure, untarnished by me or any brush with reality. Her brother, however, knew what was going on. He had worked at the Lipik stables for two years prior to becoming one of Richard’s contacts. Nazer had been there during the shelling and grenades, had seen several stallions felled by the smoke, and had barely escaped with his life. Back home now, he was working with us as well as he could without raising too much suspicion as we camped out in Travnik for a while with the UNHRC aid brigade, continuing to seek out the Lipizzaners’ trail. At this point we knew they were somewhere in Serbia, moving northward.

We met Enesa when Nazer invited us to his parents’ home one afternoon for tea with cheese and olives. She had a photo from some fan publication of Jay and me and Dorenberg and his then current girlfriend, lined up couple to couple, and stared at me until she finally went and brought the magazine back to the table, poking her finger at the photo in question and asking if that was me, victorious in her excitement when I admitted the past connection.

After this initial meeting, I stopped by to chat with her a few times when we were in the area, ostensibly for aid drops, but it was becoming too dangerous. I knew these visits would have to end. Our cover was not holding, and Richard was sure our movements were being monitored. When their village came under fire, the Marić’s front door would be one of the first to be kicked in. We should have gotten them out of there, somehow—possibly—but they were determined to stay.

Partly to assuage my guilt over befriending this girl, then eventually bolting, I told her that once things were “sorted out” and life returned to normal, maybe I could arrange for her to visit me in the States, and maybe even meet Andy before one of his concerts. Whether or not I had the chits to do this was not clear; I felt I was being generous with things not my own, like taking some pretty thing off someone else’s mantelpiece, and announcing, ‘Here’s a gift from me.’ But it didn’t matter because I knew these promises would not be kept, these dreams would never materialize. The cessation of violence, Enesa visiting America, Enesa meeting Andy; it was all pie in the sky.

But I pushed this fantasy along as the road looked bleaker and bleaker. Always the contrarian, Enesa seemed surprisingly hesitant about the whole idea, reluctant even. “Well, don’t you want to meet him?” I asked her one day. She gave me her look.

“It’s not that. It’s like staring up at the stars while stuck here on the ground, and suddenly shooting up into space, flying through the blackness.” Enesa made a wavy motion with her hand. “So far away, and now close. You would never want to come down. But you do.” She stopped and turned her head to stare out her window. “How could you go out the next night and look up at the sky? What if it didn’t happen again? I’m not that brave. What if it never happened again?”

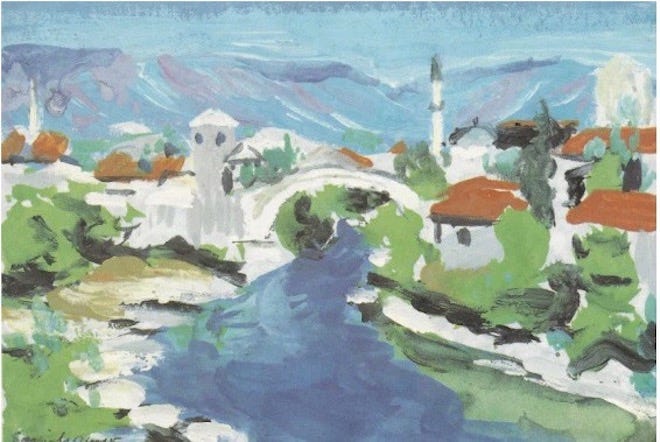

Image: Pie in the sky. Source: Scene from Bosnia. Card sold to help victims of Bosnian war, circa mid-1990s. Artist: Samiah Omar